- In the first story of the project “The AI Factory Floor,” in collaboration with Pulitzer Center’s AI Accountability Network, we show how Meta uses artificial intelligence training for content moderation.

- The lack of guidance results in inconsistent classifications and can be critical for content such as floods in Rio Grande do Sul, in Southern Brazil.

- Internal documents show that this work, done through the Appen platform, aims to create an automated system to “identify and match evidence with disinformation.”

- Payment is about US$ 0.09 per task. Moderators have 1 hour to moderate at least 40 pieces of content.

- Moderators are frequently exposed to disturbing content, such as violence and political disinformation, without support.

Erica is a São Paulo native who, since February, has worked on a platform to train Meta’s artificial intelligence. In recent weeks, her task queue has been consumed by one subject: the floods in Rio Grande do Sul. Her role is to check Facebook posts linked to websites deemed “reliable,” and to mark whether the information is true or false.

The results are used to build an automated system to “identify and compare evidence with disinformation,” according to training materials obtained by The Intercept Brazil. Internal reports, screenshots, and videos show that the job is done on an internal Meta platform, using content gleaned from Facebook and Instagram.

Plagued by fake news and potentially criminal content, the tech giant pays journalistic outlets to fact-check information and outsource content moderators. Now, Meta appears to be moving towards the final stage of automation: developing an AI to replace humans entirely.

Fake news about floods in Rio Grande do Sul has become a grave issue, hindering rescue missions and government reactions. Meta stated that it is “facilitating checkers to find and classify content as relevant,” recognizing “that speed is especially important during critical events like this.”

What the company does not divulge, however, is that the abundant and sensitive false content about the floods is ending up in the hands of Brazilian workers who receive just a few cents to classify each sensitive post. These workers exist at the end of a long chain of artificial intelligence training.

The Intercept found employees working for Meta on projects through the platform Appen, which gathers one million outsourced “collaborators” throughout the world to execute small artificial intelligence training tasks – translations, transcriptions, evaluations, and other activities.

One project called Uolo aims “to improve the quality and credibility of information circulating on social networks,” according to the job description, as well as “contribute to the creation of an automated system to identify and compare facts with disinformation,” according to the training material. The project also exists in other countries, such as Russia and Ukraine, beyond Brazil.

On Uolo, workers receive a series of posts to verify. Employees receive about 0.45 Brazilian reais for every classified post. They need to evaluate 40 posts per hour, which leaves them just over 90 seconds for each publication. After successfully completing an hour, workers receive $3.50 .

The work queue contains a smattering of everything: gambling, phony advertising, and politics, to name a few. But in recent weeks, posts about the flooding in Rio Grande do Sul have started to appear more frequently, according to reports accessed by the Intercept.

A false post claiming that Lula had refused aid from Uruguay, for example, was one that appeared in Erica’s pipeline. She checked the information on news outlets such as Folha and Uol, but was uncertain whether it was true. There was no specific company guidance on the topic, nor training; it was up to her colleagues to clear up the doubt.

“I know that it’s difficult what people are going through, but I can’t stand to see any more news from there,” Erica confessed.

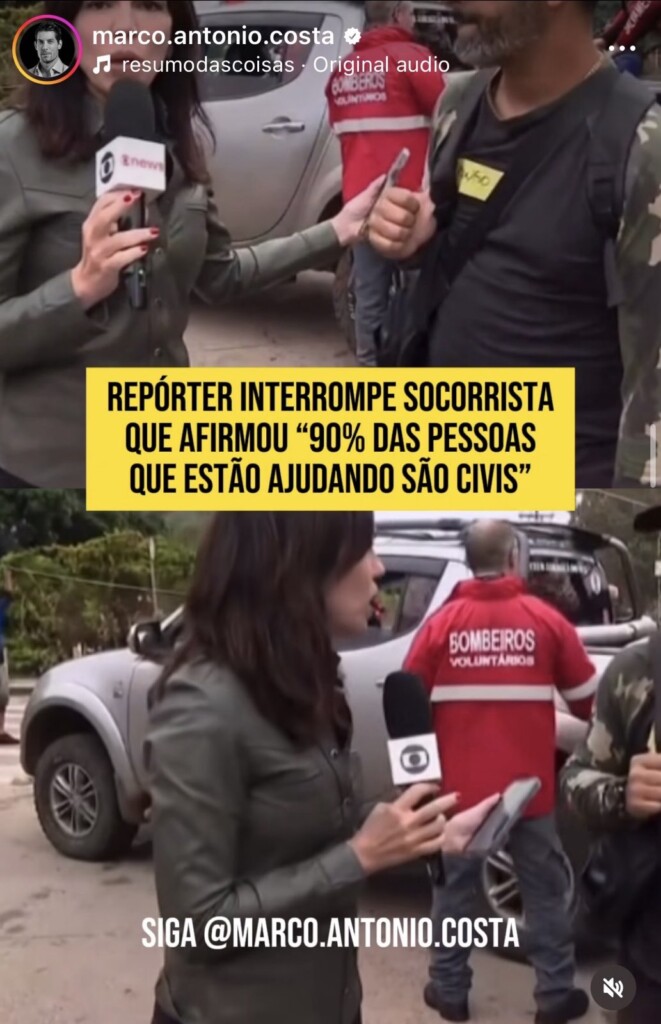

During the short time that The Intercept Brazil followed the moderators, there were posts discrediting the press, hindering rescue work, and criticism of the federal government. Erica had difficulty classifying the content. Another worker agreed: “It’s been hard to find reliable news.”

According to Yasmin Curzi, law professor and coordinator of the Media and Democracy project at Fundação Getúlio Vargas, this type of work is exhausting, and workers’ exposure to such content should have ethical and labor-rights implications. But beyond that, “The precarious situation and pressure for faster decisions to achieve metrics can lead content to not be analyzed with due care,” explains Curzi.

Big tech companies like Meta, Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, and Google accounted for over 80% of Appen’s profits last year. Over the past year, however, the multinational’s revenue has decreased revenue and it has lost significant clients, such as Google. Despitethese developments, Meta continues on with projects to train AI for fact-checking, clickbait content, and ad classification.

For Curzi, the creation of an automated fact-checking and classification system has “significant risks.” She said that, “it is still not possible to effectively automate the detection of sensitive speech that depends on context, such as disinformation.”

“Excessive automation can result in false positives – legitimate content improperly classified as disinformation – but there is also a risk of false negatives – harmful content not being identified correctly,” Curzi explained.

The Intercept sent Meta a series of questions. We asked, for example, how the training of outsourced content moderators via Appen works, how their wage is calculated, and what the objectives of the projects are. Initially, the press office in Brazil claimed to be unaware of the work with Appen; after we sent the questions, Meta did not respond. Appen also refused to answer our questions.

‘Politics has the most fake news’

Publicly, the Uolo project is framed as an “excellent opportunity for individuals who are passionate about promoting reliable information in the digital space.” The project description states that “You will be responsible for reviewing and evaluating posts, ensuring accuracy, reliability, and credibility.” There is no public mention of Meta.

Appen has strict confidentiality rules aimed at preventing workers from bringing information outside the platform and, consequently, organizing better labor conditions for themselves.

Because of this, all the reports and documents described in this report are anonymous. The Intercept Brazil had access to dozens of screenshots of internal systems that clearly delineate a relationship with Meta. The Intercept Brazil confirmed the authenticity of the posts but will not disclose them in order to protect sources.

Workers’ routine is intense, complex, and exhausting. They have an hour to evaluate the principal objective of the post – whether it is satire or intends to inform, persuade, or entertain – and whether it is potentially false. Each photo must be checked within a minute, and each video within up to three minutes.

The guidelines are part of an over 30-page PDF document adapted to Portuguese by an online translator. One of the instructions, for example, states that posts should be checked in reverse image search on Google and news sites.

The checkers must inform whether the information can “affect someone’s life” – posts on health, politics, religion and government, for example – and decide how many people could be affected. On a scale of potential negative impact, the documents describe that financial, voting, and health information contain the most potentially damaging content.

In reality, however, moderation is much more complicated. The document suggests finding a “reliable source” to confirm the information – which can be a “widely accepted authority” or one that “provides professional quality content.”

There are no specific guidelines on what quantifies a reliable source. In the groups that The Intercept Brazil followed in which workers share tips, the fact-checking website G1 was indicated as a reference.

For Curzi, minimal training can cause moderators lacking context to make “inappropriate, inconsistent decisions that can violate peoples’ freedom of expression with false positives, or put other people’s rights at risk with false negatives. This is exactly the root of low quality content moderation in Portuguese,” she explains.

“If you don’t have the context, you won’t know how to evaluate. Everything is done to keep you in the dark and say ‘oh, there was human supervision, if they didn’t know how to evaluate it, that’s their problem,'” says Rafael Grohmann, a professor at the University of Toronto and a researcher in fair labor on tech platforms.

He explained that as the chain of AI training is global – meaning tasks often come from abroad without Brazilian context –, even Meta’s Brazilian higher ups are unaware of how to properly moderate certain content.

The material offered as training to Brazilians clearly demonstrates the lack of context and nuance in content classification.

“It is essential to know if they have any guidance and training to do this work – which passes judgment on freedom of expression and has such a profound impact on the exercise of online rights,” says Curzi. “Moderation is a quasi-judicial power and needs to be treated with due seriousness by platforms.”

One of the posts available for Brazilians to moderate, for example, informed that the gas canister price dropped 13 cents under Lula’s government, with a video of the then president of Petrobras. A worker from Minas Gerais searched Google for the information, which he considered false.

“Politics has the most fake news,” said another worker in the group. The content varies, and the requirement is that the checkers dedicate 20 hours per week to the work. “Sometimes we lose a lot of time looking, researching,” said the worker, who claims to earn a minimum wage from his work as a content moderator.

For many, the work is exhausting. Errors are not allowed. “Uolo is one of the most strict projects—if you mess up, you’re out,” said one of them. “I find it very demanding for the pittance they pay,” said another.

Short on time, workers resort to ChatGPT

Érica works on two different projects. She spends the day sitting at a desktop computer – she wants to save money to buy a laptop. She wakes up early to maximize her ability to move through her task queue, and she helps colleagues with questions. She works at Uolo and on another project, called Odgen, which is a favorite among Brazilians.

Odgen follows the same logic as Uolo but focuses instead on ad classification. It’s an especially sensitive task, as ads can be another source of disinformation.

In the case of Rio Grande do Sul, a survey by Federal University of Rio de Janeiro found at least 381 fraudulent ads and 51 that contained false information on Meta’s networks.

On Ogden, evaluators must classify problematic ads as offensive or inappropriate. The company expects a batch of 40 to 60 ads to be evaluated in 1 hour. Employees receive $5 for their efforts – about 25 Brazilian reais. Workers evaluate ads in just over a minute and provide a classification. Then they move on to the next one.

One of the documents obtained by The Intercept Brazil describes how ads rejected by Instagram users are evaluated. The first step is interacting: the worker must observe the ad and react – liking, sharing, commenting, or hiding – as they normally would.

Then, the worker must decide whether he considers the ad offensive, harmful, or inappropriate, and assess whether it should continue on Instagram or not. Finally, the moderator will send feedback in the form of a short text in English, describing his feelings about the product.

All kinds of things appear on the workers’ screens, and the platforms are not responsible for any consequences.

Bruno, a worker interviewed by researcher Matheus Viana, had to assess whether there was blood, violence, and abuse in the ads. “I needed to have psychological support, a support system,” he says. “A woman I met had to undergo treatment. We need to try to minimize the impact on workers who keep watching deaths, to get the images out of their heads.”

Vitor, another worker from Bahia, told The Intercept Brazil that he has seen videos of self-mutilation and young girls without clothes, in addition to anti-vaccination ads.

There were no clear guidelines on what could pass. “You end up dealing with subjective criteria, even though they ask you to be objective,” Vitor explained.

Workers often decide how to classify a particular ad only after listening to colleagues.

“I’m always in doubt. Do you guys mark alcoholic beverage ads as inappropriate?” a worker asked. “I mark that there’s nothing wrong,” replied another. “I say that there isn’t because a lot of people drink,” said a third colleague.

Alcoholic beverage advertising in Brazil is regulated by the National Council of Self-Regulatory Advertising, and there are strict rules: people in the ads must look over 25 years-old, and there can be neither photos nor videos showing people consuming the product.

Ads for gambling also appear frequently on a variety of sites. Again, their appearance depends on the assessment of a moderator. “I mark the gambling ones as potentially misleading to make money,” said a moderator in the group. “I mark them as potentially misleading and inappropriate. And I say that the winnings shown are not real,” said another.

One of the most common gambling ads is for a betting game called Tigrinho. “I actually like it when it shows up because I already have a ready-made text for it,” said one.

In addition to gambling and betting ads, workers also frequently report ads for supplements, which use false images of Dr. Drauzio Varella, a popular physician and writer. “I give bad ratings to all of them,” says one worker. Another was hesitant. “In this case, the medicine they sell is real, but since they use a fake image to promote it I was dubious,” he replied.

Since the time to evaluate each ad is short, a tip from colleagues is to use ChatGPT, a generative artificial intelligence tool, to save time. “For gambling ads, have ChatGPT come up with five responses, for marketplace ads another five, if a link doesn’t work, another five responses,” another suggested.

Sometimes Appen offers extra hours that are distributed among workers. But generally, in this project, workers must complete at least 1 hour per day, five days a week. Those who exceed the daily limit are notified. Those who work less are also notified.

“Consultants who cannot consistently fulfill their contracted weekly hours may be removed from the project,” says one of the project’s internal documents.

If the worker for any reason cannot work for the full five days, Appen requests that they refrain from working for the entire week. “Partial weeks have a more negative impact on our overall objectives,” the document says.

On average, Vitor is able to get through between 38 and 40 ads per hour. To receive payment, invoices must be submitted by the 2nd of each month, and the platform used for the transfer charges an annual fee of US$35 (or 175 Brazilian reais) from each worker. In February, he couldn’t work due to platform issues. He usually manages to make R$500 per month. “You can’t call it work,” he says.

A VIRADA COMEÇA AGORA!

Você sabia que quase todo o orçamento do Intercept Brasil vem do apoio dos nossos leitores?

No entanto, menos de 1% de vocês contribuem. E isso é um problema.

A situação é a seguinte, precisamos arrecadar R$ 400.000 até o ano novo para manter nosso trabalho: expor a verdade e desafiar os poderosos.

Podemos contar com o seu apoio hoje?

(Sua doação será processada pela Doare, que nos ajuda a garantir uma experiência segura)