Leia esta reportagem em português →

Lea este reportaje en español

Three bullets to the head ended a presidential campaign, sending a South American nation and parts of Washington D.C. reeling. Fernando Villavicencio, a charismatic Ecuadorian politician, had been rising in the polls in the August 2023 snap elections by promising to take on the corrupting influence of violent, organized drug cartels. Less than two weeks before the election, as the candidate walked among a cheering crowd towards his car at a campaign event, an assassin shot him dead.

The brazen killing rocked Ecuador and brought international attention to the South American nation’s election. Villavicencio’s supporters quickly blamed leftist Rafael Correa, president from 2007 to 2017, and his party for the candidate’s assassination, without evidence.

Then, the U.S. government got involved: First, the State Department announced a multimillion-dollar reward for information leading to those who planned the killing, and later, the FBI sent a team of agents to investigate the assassination.

Now, leaked private messages purportedly sent by Ecuadorian Attorney General Diana Salazar, and reviewed by Drop Site News and The Intercept Brasil, reveal why the U.S. invested so many resources to investigate the candidate’s assassination: according to Salazar’s purported messages, Villavicencio was a U.S. government informant. And Salazar, who was apparently in close contact with the U.S. ambassador, helped shape a public narrative that the leftist party was to blame for the killing—a maneuver that successfully kept the Correaistas from returning to power and dramatically accelerated the Ecuadorian state’s staggering descent.

The sensitive revelation is one of many that comes from the series of leaked chats between a former Ecuadorian assemblymember and an account he says was Salazar.

Drop Site is the first English-language outlet to obtain complete access to the explosive chat records that reveal the inner workings of a politically motivated attack on the leading leftist political party, all with the blessing of the U.S.

Some of the messages have been reported on by the Ecuadorian media, which has buried the story. The foreign press has largely ignored the leaks, which provide a rare and intimate look into an example of the underhanded, U.S.-backed right-wing playbook. This playbook has, over the last decade, duped much of the media, promoted reactionary movements and anti-political sentiments, rolled back social gains, and wreaked political havoc in Brazil, Peru, Guatemala, Argentina, Bolivia, Venezuela, Honduras, and beyond. Former president Donald Trump has also flirted with it, by attempting to use the U.S. Justice Department to go after political adversaries.

The Salazar messages are now the subject of an investigation by Salazar’s colleagues and she is currently facing impeachment for “breach of duties” within the National Assembly, a process primarily led by the left-wing political party. In May, a Florida-based criminal attorney, representing an Ecuadorian man implicated in one of Salazar’s investigations, wrote a letter to the House Judiciary Committee and the Justice Department, claiming that the messages “violate several federal laws” in the U.S. The attorney recommended the U.S. blacklist Salazar for revealing “highly sensitive and confidential information” from U.S. law enforcement agencies.

Salazar and her attorney did not respond to a request for an interview nor to a detailed list of questions from Drop Site and The Intercept Brasil. She has never denied that the chats belong to her, but Salazar has called the entire ordeal a political circus, saying that it is an attempt to “contaminate” one of her major investigations. In March, when the assemblymember began releasing the chats, Salazar said on X, formerly known as Twitter: “I will remain focused on what is important, desperation knows no bounds. They will not distract our attention.”

Since being appointed in April 2019, Salazar has become one of Washington’s strongest allies in the country, with U.S. officials championing her as a crusader against corruption: the State Department presented her with an award; later this year, she’ll receive another award from the Woodrow Wilson Center; and Samantha Power, the USAID administrator, wrote a glowing profile of Salazar for TIME magazine. U.S. support is essential for a non-leftist with political aspirations. With the exception of Correa’s presidency, the bilateral relations have historically been so tight that in 2000 Ecuador even went so far as to replace its own currency with the dollar.

Salazar has led a series of high-profile prosecutions to—as she has claimed—root out corruption in Ecuador, whipping up a national fever of anti-corruption and anti-political sentiments. Among the targets of investigations include the last three former presidents: Rafael Correa, Lenín Moreno, and Guillermo Lasso. (The impeachment case laid out by her political opponents accuses her of strategically accelerating cases against leftists while delaying others, including the ones implicating Lasso and Moreno, both right-wingers.)

Now, the tranche of hundreds of private messages show Salazar may have revealed sensitive information from the investigations, lending credence to allegations by Correistas that she engaged in a pattern of politically motivated actions, including aggressively pursuing cases against left-wing politicians while simultaneously delaying cases against more pro-U.S. right-wingers.

The messages, exchanged with Ronny Aleaga, a close confidante formerly of Correa’s party, call into question Salazar’s prosecutorial ethics and impartiality. The relationship between Aleaga and Salazar, ostensible political rivals, remains a source of mystery and intrigue in Ecuador. He told Drop Site their relationship was not romantic, but one of intimate confidence. Whatever the case, the messages, in which Salazar’s purported contact is registered as “Seño,” read as two people close to each other swapping political information, with the relationship going through twists and turns as Aleaga’s role in her investigations fluctuates. In an interview, Aleaga claimed he did not know why Salazar was sharing sensitive information regarding her investigations.

“I am also confused,” Aleaga told Drop Site. “If we were political adversaries, why was there this communication? I’m not sure.”

Aleaga provided Drop Site with conversations exchanged on an anonymous, private messaging platform that he recorded and saved. Drop Site and The Intercept Brasil also accessed other sensitive chats submitted as evidence in a separate criminal investigation. Overall, we reviewed over 1,500 private messages, spanning mostly from March 2023 to March of this year.

The release of these messages comes amid a defining moment in Ecuadorian history. Not long ago, Ecuador was in many ways the envy of Latin America. Today, economic freefall, gutted social spending, and political violence by increasingly brazen narco gangs are tanking the popularity of its right-wing president, heir to a billionaire banana fortune.

As narco violence lays bare the country’s political unraveling, two figures are attempting to seize the crisis and define the moment: current president Daniel Noboa has chosen a hard-line, U.S.-backed militarized approach to combat organized crime and Salazar continues to disrupt the political establishment by pursuing investigations she says are related to corruption and drug trafficking.

The causes of such a dramatic reversal of national fortunes are inevitably multifaceted, but Ecuador’s fate follows a specific pattern that has roiled many countries in the region in recent years—oftentimes with secretive support of the U.S. government, ultimately benefiting U.S. corporations and their local right-wing allies.

Among the allegations emerging from the leaked messages:

- Salazar may have delayed an investigation into businessmen linked to former right-wing president Guillermo Lasso to harm left-wing candidates during the 2023 snap elections.

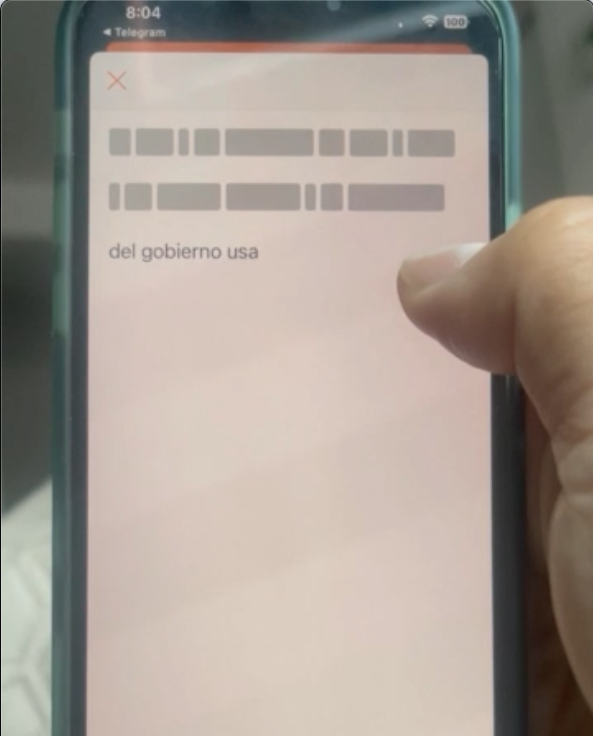

- Salazar admitted the U.S. government did not want Correa’s Movimiento Revolución Ciudadana, or Citizen Revolution Movement party (RC, by its acronym in Spanish) to win the 2023 elections. “They want RC’s head,” “Seño” wrote.

- Salazar warned Aleaga of a looming investigation into his alleged corruption, and encouraged him to flee Ecuador prior to a warrant for his arrest.

- Salazar claimed that assassinated presidential candidate Fernando Villavicencio was a U.S. government informant before encouraging Aleaga to become a cooperating witness for U.S. prosecutors.

- According to the messages, for months, Salazar knew that a criminal group was responsible for the Villavicencio murder. Despite knowing this, Salazar’s office ran with the theory that the murder was orchestrated by Rafael Correa and his allies, allowing accusations against Correa to circulate, potentially playing a deciding role in the tight 2023 snap elections.

- Salazar said she suspected the FBI deleted sensitive information from Villavicencio’s phone, during their investigation into the murder, before providing the contents to Salazar’s office, which “Seño” referred to as “procedural fraud.”

- Salazar may be using her office to punish a prominent former judge who acted against U.S. government law enforcement interests.

Salazar’s “Secretive” Relationship

Aleaga has said publicly that between 2021 and early 2024, he and Salazar had a “secretive” relationship. Throughout that time, he said, he exchanged messages with Salazar through an encrypted platform called Confide, which deletes messages soon after they are read. As Aleaga received messages, he used another phone to video record the incoming chats. A forensic analysis ordered by Aleaga and reviewed by Drop Site confirms the messages came to Aleaga’s personal phone.

Ahead of the October 15, 2023 second round of the snap election, Salazar visited the U.S. ambassador at his residence for a dinner, and later “Seño” texted Ronny Aleaga details. She revealed in messages to Aleaga that there were three separate FBI field offices handling the Villavicencio case: New York, Houston, and Miami.

10/9/2023 7:00:44 AM

Seño: Esto es heavy. Hay 3 oficinas de fbi investigando el tema. 3 oficinas federales. División Miami, NY y Houston.

[Translation: This is heavy. There are 3 FBI offices investigating the matter. 3 federal offices. Miami division, NY, and Houston.]

She added in a text that the U.S. was concerned the Correaistas were rising in the polls and might return to power.

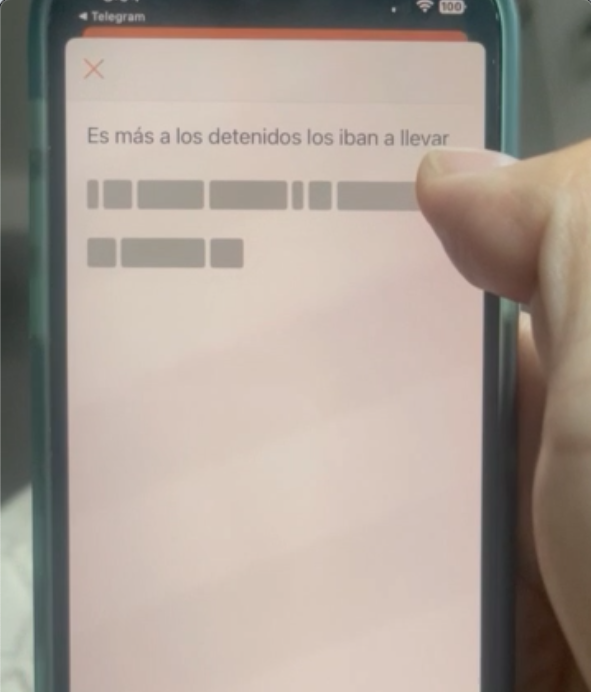

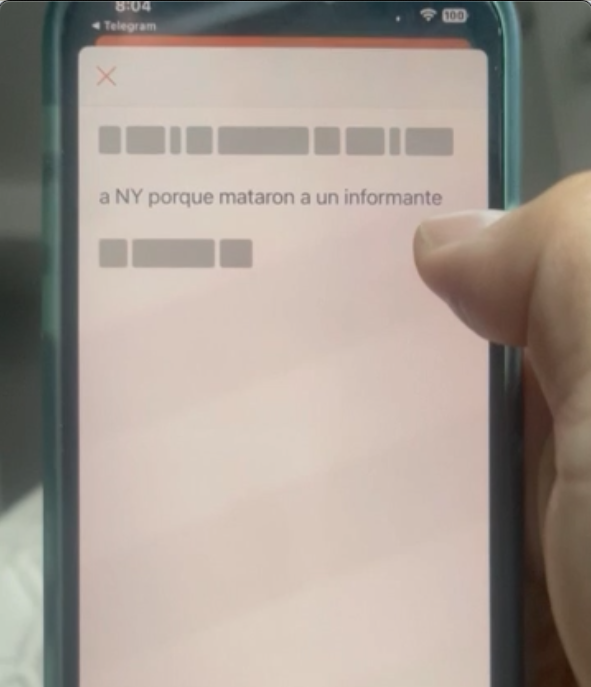

Minutes later, “Seño” made the claim that Villavicencio had been a U.S. informant. She writes that seven of the suspects in Villavicencio’s death, who had been murdered days earlier in prison, were going to be sent to New York because they had “killed an informant of the U.S. government.”

10/9/2023 7:04:52 AM

Seño: Es más a los detenidos los iban a llevar a NY porque mataron a un informante del gobierno usa

[Translation: Moreover, the detainees were to be sent to NY because they killed an informant of the U.S. government.]

During that same conversation, “Seño” shared with Aleaga details of a supposed witness’s testimony, who was allegedly aware of behind-the-scenes planning of Villavicencio’s assassination. The Villavicencio family attorneys did not respond to a detailed list of questions for this article. According to the account, “indeed it was the leaders of Los Lobos” who ordered the hit on Villavicencio, which had been planned for a month. Los Lobos is one of the biggest criminal groups in Ecuador, allegedly allied with Mexico’s powerful Jalisco New Generation Cartel, and is notorious for drug trafficking, illegal mining, and other criminal acts.

In the messages, she clarified that two mid-level leaders of Los Lobos, Carlos Edwin Angulo Lara, alias El Invisible, and Darío Gabriel Suárez Bedón alias El Chino Onda, were behind Villavicencio’s killing. Angulo Lara was just sentenced to 34 years in prison for his role in the assassination. Suárez Bedón, although implicated in the case, was not formally charged and is currently serving time in prison for the murder of a high-profile Ecuadorian attorney.

The news that Los Lobos was behind the assassination, not Correa’s party, may have played a deciding role in the election—but, publicly, Salazar allowed her previous leak implicating Correa to stand.

10/9/2023 6:53:15 AM

Seño: Que esto planificaron un mes atrás, que era un político de alto valor y que como habían tratado de hacer esto en junio y no pudieron ni querían fácilmente. Por eso ingresa el invisible, originalmente el que estaba encargado de hacer todo era el Chino algo, quien mandó a matar a Harrison Salcedo.

10/9/2023 7:14:37 AM

Seño: Efectivamente fueron los líderes de los lobos

10/9/2023 7:15:09 AM

Seño: Cuando ya quedaron muy en evidencia les hicieron salir a desmentir. Pero ese Chino y el Invisible son de los lobos

10/9/2023 7:16:01 AM

Seño: Ellos hicieron llamada con todos, los 30 que participaron para darles instrucciones y les explicaron la necesidad de desaparecerlo’

[Translation: That [they] planned this a month back, that he was a high-value politician and how they had tried to do this in June […] That’s why The Invisible enters the scene, the one originally in charge of doing everything was this El Chino guy, who ordered Harrison Salcedo be killed]

[Translation: Indeed it was the leaders of Los Lobos]

[Translation: When they were very much in evidence they made them come out to deny it. But this Chino and el Invisible are with Los Lobos]

[Translation: They made calls to everyone, the 30 that participated to give them instructions and they explained the necessity of disappearing [Villavicencio]]

From prison, El Invisible took over the plot from El Chino, who had previously ordered the killing of Harrison Salcedo, a former lawyer for ex-vice president Jorge Glas and members of the Choneros gang, Los Lobos’ main rival. Additionally, “Seño” claimed that El Chino and El Invisible made calls and gave the others instructions.

10/9/2023 7:16:46 AM

Seño: Ellos dieron la orden desde la carcel

[Translation: They gave the order from jail]

Despite having this information at least weeks before the election, Salazar never publicly contradicted the leak from her office implicating Correa. It is not the only case Salazar slow-rolled around this time.

In several messages to Aleaga, “Seño” revealed her anti-Correa bias, including as it applied to one of the most significant cases Salazar has worked on, implicating right-wing then-president Guillermo Lasso. But she delayed the case for explicitly political reasons, the leaked chats show. In a September 29 text she writes that the case would only move forward after the fast approaching second round of the 2023 snap elections, so as to avoid helping Correa’s RC party in the general elections. The right-wing Noboa would go on to defeat RC’s Luisa González by a margin of only 3.66 percentage points.

9/29/2023 12:58:14 PM

Seño: Tráfico de influencias, de hecho voy a procesar después de elecciones, antes no para no ayudarles a Uds, GL [then-president Guilermo Lasso] ya sabe que me lo cargaré a su cuñado.

[Translation: Influence peddling, in fact I will prosecute after the elections, not before, in order not to help you, GL [then-president Guilermo Lasso] already knows that I am going to get his brother-in-law.]

Lasso was elected in 2021. Two years later, members of his inner-circle — including his brother-in-law, a high-profile businessman — were accused of running a corruption scheme, and of having links to Albanian organized crime groups. The National Assembly officially began impeachment proceedings, but to avoid impeachment, Lasso declared a “muerte cruzada,” a constitutional measure that dissolved the National Assembly and triggered general elections.

The leaked messages suggest that the U.S. embassy shared the anti-Correa view of the political situation in Ecuador. The embassy, according to texts a day earlier, was concerned about the RC’s performance in the polls and potential victory in the elections.

9/28/2023 9:07:58 PM

Seño: Quieren la cabeza de RC

9/28/2023 9:22:32 PM

Seño: Dicen que uds están subiendo

[Translation: They want RC’s head]

[Translation: they say you all [RC] are going up in the polls]

Days later, “Seño” reiterated the U.S. embassy’s position about the election.

10/9/2023 7:01:15 AM

Seño: Ellos saben que si uds ganan todo queda ahí.

[Translation: They know if you all [RC] win everything ends there]

Who’s afraid of Rafael Correa?

In 2007, when Rafael Correa became president, the U.S. warned he would join the likes of leftist bogeymen Fidel Castro, Hugo Chavez, and Evo Morales, moving the country toward a communist dictatorship.

Then-Ambassador Linda Jewell wrote to the U.S. Secretary of State, in a 2006 cable later published by WikiLeaks, to warn that “none of the top contenders would affect [U.S. government] interests as thoroughly as Rafael Correa.”

“We would expect Correa to eagerly seek to join the Chavez-Morales-Kirchner group of nationalist-populist South American leaders,” the ambassador continued.

Correa did tighten bonds with Cuba, Bolivia, and Venezuela, and was critical of U.S. dominance in the region, particularly its reliance on International Monetary Fund and World Bank pressure to cut taxes, regulations, and public services. Instead, Correa doubled social spending and cut inequality substantially while also trimming the nation’s deficit and stiff-arming the IMF. He also got rid of a U.S. military base in Ecuador.

Despite the 2008 global financial crisis and the 2014 collapse in oil prices, Ecuador saw steady economic growth that significantly outpaced prior decades and was consistently ranked one of the safest countries in Latin America. Correa left office in 2017—undermining the U.S. claim he’d become a dictator—endorsing Lenín Moreno, who won on the Correísta record easily.

While Donald Trump is often talked about as something of a non-interventionist, the hands he hired to run his Latin American policy had tight links to right-wing forces ensconced in Miami who’d been working with Republicans since the Reagan era to overthrow social democratic governments and replace them with right-wing strongmen more pliant to U.S. and corporate interests. In Brazil, Bolivia, and Honduras, U.S.-backed right-wing movements engaged in rampant electoral fraud and/or malignant prosecution of political adversaries, as in the case of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in Brazil. The U.S. also openly backed regime change plots, including a successful 2019 coup in Bolivia, and unsuccessful attempts in Venezuela.

In Ecuador, the right-wing lurch came in the form of a stunning about-face from Moreno, who, once elected, disavowed the movement that had brought him to power and allied instead with the U.S. and the Ecuadorian right. Social spending was slashed and power distributed to an oligarch faction linked to drug trafficking. Violence and instability rose in tandem with organized crime. The U.S. government increased its support to Ecuador, providing funding, aid, and security training.

Moreno undid many of the progressive reforms put in place by Correa. Correistas split from Moreno and organized RC, a new, social democratic political party. Since then, members of RC have accused the Ecuadorian government, under the presidencies of Moreno, his successor Lasso, and now current president Daniel Noboa of pursuing underhanded political attacks to prevent RC from democratically returning to power.

The most aggressive case of alleged politically-motivated prosecutions attacked Correa himself in 2020, accusing him of taking bribes. Correa won asylum in Belgium, but was convicted in Ecuador on thin evidence. He was sentenced in absentia of “psychic influence” over other public officials and given eight years in jail.

That brings us to Diana Salazar, the main subject of this investigation. Salazar is an Afro-Ecuadorian woman from Ibarra, a small provincial capital near the Colombian border. She started her career at the Attorney General’s Office in 2001 and made her way up the ranks to the top spot in 2019 in a contentious process, at a time when Moreno was overhauling the judiciary to purge pro-Correa elements. Salazar has made a name for herself with bold and sweeping investigations to purportedly root out corruption and narcotrafficking networks in the country.

Yet both have flourished as the country’s right-wing lurch has since lost its balance. Since Moreno’s presidency, violence has only worsened with the increase of U.S. security support fueling Ecuador’s war on drugs—following a well-established pattern in other Latin American countries. Narcotrafficking gangs brought international attention in January when they led a prison break and occupied a TV station while it broadcast live on air. Then the Noboa government stunned the world community with a commando raid of the Mexican embassy in April to drag out Jorge Glas, Correa’s vice president, to whom Mexico had offered political asylum. In recent years, crime has soared and the economy has collapsed, the predictable but shockingly fast result of the U.S.-supported austerity measures in Ecuador, hollowing out the state’s capacity.

Throughout this tumultuous period, Salazar has held an important office with great power to tackle—or perpetuate—the nation’s problems. “She is a key player for the right-wing groups in the country,” said Carla Morena Álvarez Velasco, a university professor and researcher at the Ecuadorian Institute of High National Studies (IAEN), who specializes in security matters. “She’s also a key player for the North American government in this country.”

In recent years, questionable prosecutions targeting left-wing politicians have become a pattern across Latin America, following a playbook created and supported by the U.S. government. In Peru and Argentina—among others—a pattern of U.S.-backed prosecutions targeted left-wing politicians and helped pave the way for regime change. The Salazar revelations also echo one of the most egregious examples of U.S.-backed prosecutorial misconduct in the region: explosive reporting published by The Intercept Brasil in 2019 based on another trove of leaked messages, which revealed serious ethical violations by a Brazilian judge and prosecutors, who colluded with each other to pursue political attacks against Lula da Silva in an effort to prevent his return to the presidency in 2018. The judge, Sergio Moro, hailed by the U.S. as an anti-corruption champion, has since fallen into disgrace after evidence of his bias eventually led the Supreme Court to throw out his judgment that landed Lula in prison.

According to the messages reviewed by Drop Site and The Intercept Brasil, the practice of U.S.-backed politically motivated prosecutions has reached Ecuador.

“Diana Salazar has been spearheading the most brutal persecution and has been the principal author of the judicialization of politics in Ecuador,” said Andrés Arauz in a statement. Arauz is the executive secretary of Revolución Ciudadana, Correa’s left-wing political party in Ecuador. “The political persecution against ex-president Rafael Correa, to impede his presence and participation in Ecuador’s political life, has been particularly bloody and has done great harm to progressivism, democracy, and the state of law in our country.”

“Attorney General Salazar, since her irregular appointment and through the latest raids, has been a clear instrument of the political and geopolitical project of ‘de-Correaization’ and the fight against progressivism in Ecuador,” Arauz added.

Informants, Accusations, and the FBI: Villavicencio’s Assassination

The murder of Fernando Villavencio had a major impact on the outcome of the 2023 elections. Since Villavicencio had been critical of Correismo and the party, political opponents—including the candidate that replaced Villavicencio—began fueling the rumor that Correa orchestrated the assassination. As the rumor spread, Luisa González, the candidate for RC who had been in the lead, began dropping in the polls, helping lift Daniel Noboa, the 35-year-old heir to a banana fortune, to the presidency.

There was never any evidence that the perpetrators of Villavicencio’s assassination had any ties to RC. Villavicencio’s widow and sister initially said the state was partially responsible, and blamed the Lasso government for not offering sufficient protection, despite the multiple threats on his life. In addition to the seven suspects later murdered in prison, a wounded suspect who was apprehended at the scene died shortly afterward in police custody, under mysterious circumstances.

Nearly a week before the October 20 presidential runoff, Villavicencio’s widow and Villavicencio’s replacement claimed that they had received a leak from Salazar’s office on the testimony of an alleged “protected witness,” who blamed Correa and “his government” for Villavicencio’s killing. (Correa has been out of government since 2017.) Salazar never came forward to contradict this alleged leak from her office, despite having denied the veracity of different rumors about the case in the past.

The accusation rocked the campaign and sent the left plummeting in the polls. The question of responsibility would come to dominate the conversation around the election, and the implication that Correa’s party had been involved helped sink them at the polls in mid-October. “Seño” claimed that she and the U.S. ambassador to Ecuador, Michael Fitzpatrick, had candid and private conversations about the election and the killing of Villavicencio. The State Department did not respond to a request for comment.

Villavicencio, a former journalist later elected to the national assembly, had long been rumored of being a U.S. government asset. During a 2016 interview, Villavicencio made sarcastic quips about his ties to the CIA and FBI. He was also accused in Ecuador of leveraging confidential information in political maneuvers against adversaries.

The witness testimony described in the October messages was partially read aloud at a hearing on February 27 of this year, and it matches what “Seño” had texted Aleaga months earlier. In the testimony, the witness claimed that El Chino Onda, the imprisoned mid-level leader of Los Lobos gang, had led the plot. A previous attempt to kill Villavicencio had been abandoned because it was deemed too difficult and those involved were unwilling to proceed. Following this, El Invisible, another imprisoned mid-level leader of Los Lobos gang, took over with his own team of Colombian hitmen. When asked about the motives behind the assassination, the witness testified it was done out of fear Villavicencio would toughen criminal sentences if elected.

Seño told Aleaga she was deeply concerned about what the U.S. might learn from Villavicencio’s phone. That, too, was backed up by later developments. In November, members of Villavicencio’s family shared that they handed his phone directly to the FBI, due to a lack of trust in Ecuadorian institutions to carry out the investigation. Later, the FBI handed Ecuadorian officials a device, purportedly with the phone’s contents.

Conversations between Aleaga and “Seño” from November suggest Salazar may have received the phone’s contents in a data dump from the FBI, and that she suspected the FBI had erased some information. “Procedural fraud,” she wrote.

11/14/2023 9:48:37 PM

Seño: En justamente lo que dije a fiscales y fbi aquí

11/14/2023 9:48:54 PM

Seño: Que por más información relevante esa será prueba cuestionada

11/14/2023 9:54:30 PM

Seño: EntregRon un volcado. Igusl ya la tengo

11/14/2023 9:54:31 PM

Seño: Una copia de la nube

11/14/2023 9:54:33 PM

Seño: No el equipo

11/14/2023 9:54:34 PM

Seño: Y ahí pudieron borrar

11/14/2023 9:54:36 PM

Seño: Fraude procesal

[Translation: It’s exactly what I told prosecutors and the FBI here]

[Translation: That even though it could be relevant information it will be questioned evidence]

[Translation: They handed over a [data] dump. I already have it.]

[Translation: A copy of the cloud]

[Translation: Not the device]

[Translation: And there they could have erased]

[Translation: [That’s] procedural fraud]

The legislative committee investigating Villavicencio’s killing issued a report with its findings in mid-June. It found that Lasso and the National Police may have committed criminal and administrative infractions by failing to protect Villavicencio. The committee notes that Lasso had failed to carry out his constitutional duties and that Villavicencio’s assassination could have been avoided. The report further determined that the prison authority had committed “serious omissions” that allowed the individuals arrested for Villavicencio’s assassination to be murdered in prison.

During a June hearing, the prosecution played a pre-recorded video of the same protected witness, whose testimony had been leaked prior to the election, saying there was a $200,000 price tag on Villavicencio’s head and that “the Correa government” ordered the assassination. However, the witness had come out months earlier in a video posted on TikTok to say he had been pressured to incriminate Correa.

Villavicencio’s widow has begun to doubt the strength of Salazar’s case, pointing to contradictions between the protected witness’s testimony and Salazar’s statements. Villavicencio’s widow said Salazar claimed the contract to kill Villavicencio was worth $1 million and that it included a hit on a second target — Salazar, herself. Villavicencio’s widow also claimed in June to have knowledge of recorded FBI interviews with the seven murdered suspects, who were reportedly going to be taken out of the country as part of an agreement. This matches a message from “Seño” to Aleaga in which she says that those detained were going to be taken to New York because they had killed a U.S. informant.

In mid-July 2024, five people were sentenced for the murder of Villavicencio, all tied to the Los Lobos gang and with no known RC connections. One year after Villavicencio’s murder, his family remains angry with Salazar, demanding a more aggressive prosecution.

Aleaga, the assemblymember, was formally implicated earlier this year in a high-profile anti-corruption investigation, called the Metastasis case, in which public officials and members of the judiciary have been accused of accepting bribes from a prominent drug trafficker in exchange for favorable rulings. But before Aleaga’s indictment dropped, “Seño” warned Aleaga his arrest was imminent, and encouraged him to flee the country to avoid arrest.

“Alright. I ask you, leave the country. Get yourself to a safe place, it’s the only way, then you can decide what to do,” she wrote to Aleaga, later implying she would help him organize a defense: “We have to develop a strategy.”

In an interview, Aleaga told Drop Site that the relationship with Salazar was a rollercoaster of emotions. On one day, he says, she would be friendly and offer help, assuring him of a favorable outcome in the case. On other days, she would say the evidence against him was “overwhelming” and threatened and intimidated him. Aleaga says he began recording all of the messages for his own protection, and doubled-down on the recording when the Attorney General later began to threaten and intimidate him, in relation to the Metastasis case and investigations into the RC. Aleaga has publicly stated that the charges against him are false, and fled Ecuador after Salazar’s purported warnings. He is now considered a fugitive.

Aleaga began going public with his revelations in a series of videos posted on X, formerly known as Twitter, and Instagram in March. While they generated a great deal of media interest and controversy in Ecuador, they have largely been ignored by U.S. media.

Aleaga requested a forensic analysis of his videos by the independent, Florida-based company Digital Forensics Now (DFN), in response to his allegations of intimidation, harassment, and blackmail by Salazar. Drop Site reviewed the forensic analysis from earlier this year.

“The scope of the investigation consisted of investigating two cellphones and analyzing communications and interactions between user account ‘RA’ (Mr. Aleaga) and ‘Seño’ (Mrs. Diana Salazar) through the encrypted messaging application, Confide,” the DFN forensic report reads. “Based on the evidence available, DFN concludes that there were recorded communications between the ‘RA’ and ‘Seño’ accounts over a prolonged period of time discussing politics, criminal cases, and other personal affairs.”

Aleaga also says that revealing these private messages is necessary for the Ecuadorian public to understand who sits in one of the most powerful positions in the country.

“I’m not saying I have not messed up — of course,” Aleaga says. “Without revealing these private chats, there is no way to reveal who Diana Salazar truly is.”

Ecuador, under the leadership of right-wing opponents of Correa and the RC since 2017, has issued arrest warrants for Correa and several prominent RC politicians in connection to Salazar’s investigations.

“[Salazar] serves the interests of the right,” said Alvarez, the professor and expert in Ecuadorian security matters. “Today it’s Noboa. But yesterday it was Lasso, and before yesterday, it was Lenin Moreno. It’s a line, an ideological continuity, that transcends those major characters.”

Rafael Correa’s “Psychic Influence”

Correa was in office from 2007 to 2017, during a period in which Ecuador was seen as an island of peace, surrounded by neighbors with long-lasting civil conflicts. In 2009, Correa’s government got rid of a U.S. military base in Ecuador, a move that current president Daniel Noboa blames as the cause for the rise of drug trafficking and violence.

In 2019, Salazar’s office launched an investigation called “Bribes 2012-2016,” which accused Correa of running a corrupt network of officials that collected over $7 million in bribes. Correistas allege the case was based on flimsy evidence. During the investigation, a Correa assistant turned over a notebook she said included contemporaneous evidence that Correa had taken bribes, but it was soon shown the notebook hadn’t been printed until 2018, several years after the allegedly contemporaneous notes were taken. It was accepted as key evidence regardless.

Despite the purported weak evidence in the case, Correa himself was found guilty of “psychic influence” over public officials, inducing them to engage in bribery. He was sentenced to eight years in prison in absentia for that witchcraft, and was banned from participating in national politics for the duration of his sentence. He was granted asylum in Belgium, and due to the political nature of the case, Interpol has refused to issue a red alert for Correa’s arrest. He appealed the guilty verdict, and although it was expected to be a lengthy process, the entire appeal process took only 17 days, with the judges—who had been appointed by Moreno—upholding the verdict.

Another prosecution, the Sinohydro Case, accused a network of officials, including former president Moreno, of receiving bribes in exchange for allowing a hydroelectric project to continue operating. That case is still open, and is part of a right-wing public relations effort to accuse Correa of selling out the country to China—again, a strategy that aligns neatly with U.S. interests in the region.

The prosecution of Correa deeply polarized Ecuador, with many accusing Salazar of pursuing the case for purely political reasons, pointing at the speedy nature of the proceedings. While the case against Correa and his allies has been closed, the others implicating former president Moreno and former president Lasso’s allies are still ongoing.

Metastasis Case

In the Metastasis case, one of the most significant investigations of Salazar’s career, the Attorney General went after numerous officials, accusing them of having received bribes from drug kingpin Leandro Norero, who helped launder money for, and had connections to, several criminal organizations, including Los Lobos. Norero, who allegedly gave money to officials in order to continue running his operations from prison, was killed in prison in 2022. Salazar called the Metastasis investigation in Ecuador “the biggest in history against corruption and drug trafficking.”

Salazar has based the case largely on text messages allegedly found on Norero’s phones. Recently, a witness in the case, who was allegedly Norero’s prison cellmate, provided testimony, saying Correa had video-chatted with Norero while he was in prison, but no concrete evidence of any such calls have been presented.

Before he fled the country, Aleaga was formally implicated in the Metastasis case. He was accused of corruption in March, nearly two years after being photographed in a Miami pool with another Ecuadorian fugitive linked to Norero. Prosecutors in Salazar’s office have accused Aleaga of being the alias “El Ruso”—the Russian—mentioned in some of Norero’s messages and of acting on Norero’s behalf in the National Assembly. Aleaga has consistently denied this. “Seño” told him she believed the RC was hanging Aleaga out to dry, and encouraged him to become a cooperating witness—not just for the Ecuadorian government, but for the U.S. as well. In the messages, Salazar allegedly explains she has connections to prosecutors in Florida, and that by becoming a cooperator with both countries, he could even have his sentence reduced by 90 percent.

3/13/2024 4:26 PM

Seño: Le interesaría hacer cooperación eficaz?

3/13/2024 4:29 PM

Aleaga: Cuáles serían las condiciones?

3/13/2024 5:11 PM

Seño: Bajar la pena.

De hasta el 90%

Ingreso al sistema de protección

Su organización lo dejó solo

Sálvese

3/13/2024 5:15 PM

Aleaga: Pero ni siquiera soy culpable 😢 Y cooperador sobre que tema? Mejor dicho a quien tengo que tirar al agua ?

3/13/2024 6:23 PM

Seño: Jamás digo lo que tiene que decir.

Simplemente Ud elige lo que considere

3/13/2024 7:38 PM

Aleaga: Le soy honesto, mejor esta la propuesta de sus amigos gringos.

3/13/2024 8:03 PM

Seño: Tengo que conversar con los fiscales, dependiendo del Estado donde esté. Florida es el más fácil porque ahí tengo los fiscales y quienes trabajan conmigo.

3/13/2024 8:03 PM

Seño: Podría pedir que haga una cooperación conjunta. Pida eso ud y me llaman. Yo allá no puedo hacer acciones individuales.

[Translation: Seño: Would you be interested in cooperating effectively?

[Translation: Aleaga: What would be the conditions?]

[Translation: Seño: Reduce your sentence. Up to 90%. Enter the protection system. Your organization left you alone. Save yourself]

[Translation: Aleaga: But I’m not even guilty 😢 And cooperate regarding what topic? Better said, who do I have to throw under the bus?

[Translation: Seño: I will never tell you what to say. Simply, you decide what you consider important.]

[Translation: Aleaga: I will be honest, the offer from your American friends is better.]

[Translation: Seño: I would have to talk with the prosecutors, depending on the state you are in. Florida is the easiest, because I have prosecutors there and those who work with me.]

[Translation: Seño: You could ask to take part in a joint cooperation. You can ask that, and they will call me. I cannot take individual steps over there.]

The Metastasis case has primarily gone after judicial officials perceived to be allied with Correa, under the guise of rooting out corruption in the country’s judiciary. In December 2023, Salazar’s launch of Metastasis caused another stir when she targeted and detained Wilman Terán, the president of the Judiciary Council—an ombudsman authority tasked with oversight of her office and the courts. While in office, Terán was overseeing a process to redesign a section of the judiciary in the country. Critics of Salazar say that the evidence linking Norero to officials, including Terán, is slim, furthering public complaints of perceived political motivation.

In recent weeks, a new scandal has emerged from Terán’s testimony in impeachment hearings against him. He claims that Salazar sent “emissaries” to pressure him into ruling against Correa’s appeal in 2020, and that he now suspects evidence was hidden from him.

As part of the impeachment hearings, Terán has submitted new evidence—messages he alleges he exchanged with Salazar from a phone never seized by prosecutors. As in the case of Aleaga, Terán had his device forensically examined by experts, whose report is publicly available.

In his testimony, Terán accused Salazar of sharing confidential information about criminal cases, saying the messages in the forensic report prove the attorney general’s ethical overstep. In a series of messages in the report, dated May 11, 2023, Salazar informed Terán of an investigation into the Judiciary Council’s decision to suspend a judge from the National Court of Justice, the highest court in Ecuador tasked with interpreting law. The Council’s decision to suspend the national judge took place in response to a complaint filed by a man previously convicted of involvement in organized crime. In the messages, Salazar later told Terán that he and three other Judiciary Council members were being investigated and would be formally notified the following day.

On May 12, messages show that Salazar purportedly notified Terán that prosecutors would raid the Judiciary Council’s offices, which occurred on the same day. The investigation into the suspension and removal of the national judge, which later became a separate criminal case in which Terán and others are implicated, alleges irregularities in the Judiciary Council’s decision to suspend the national judge.

However, when Terán asked Salazar why the judge’s removal was under such intense scrutiny when other judges had been removed for similar reasons, her explanation did not mention irregularities. Rather, according to the messages Téran shared with the court, she said that the case involved important people and a parallel investigation in the U.S. Essentially, Terán and the others were being punished for giving legitimacy “to the complaint of someone investigated in a corruption scheme,” one of Salazar’s alleged messages said.

In earlier chat logs from April 11, Salazar forwarded Terán a message from an unnamed person, informing her about an upcoming hearing in the Leandro Norero money laundering case. It says that the prosecutor, Lidia Sarabia; the Financial and Economic Analysis Unit (UAFE); and the U.S. embassy “are very worried about the judge’s irregularities. Could you call the president of the Judiciary Council to express their concerns? I’ve been told that the UAFE director will call. We will, as well.”

Ecuadorian media outlets have largely ignored the contents of Terán’s tranche of messages, making little note of the striking parallels to the messages with Aleaga. Instead, the Ecuadorian press has been largely satisfied with the prosecutor’s blanket denial.

In a recent interview, Salazar said that Terán’s legal challenges against her are an attempt to delay the case, so that—once she takes a leave of absence due to her impeachment trial—there will be impunity with his case.

Last week, Salazar’s office raided the National Court of Justice to investigate two high-ranking judges. Those judges had ruled in favor of Terán’s request to be transferred to a separate prison so that he could continue building his legal defense. The Ecuadorian Association of Magistrates and Judges, which advocates for judicial independence in the country, strongly condemned the recent raid.

Ecuadorians are gearing up for new elections in 2025. The first round of Ecuador’s next general elections are scheduled for February, 2025, where Noboa will run again for the presidency.

This story was reported in partnership with Drop Site News, a new project created by some of our friends from The Intercept US. You can read the English version of this article on their site and don’t forget to sign up for their free newsletter full of exclusive reporting on U.S. politics, Israel’s war on Gaza, international affairs, and more.

JÁ ESTÁ ACONTECENDO

Quando o assunto é a ascensão da extrema direita no Brasil, muitos acham que essa é uma preocupação só para anos eleitorais. Mas o projeto de poder bolsonarista nunca dorme.

A grande mídia, o agro, as forças armadas, as megaigrejas e as big techs bilionárias ganharam força nas eleições municipais — e têm uma vantagem enorme para 2026.

Não podemos ficar alheios enquanto somos arrastados para o retrocesso, afogados em fumaça tóxica e privados de direitos básicos. Já passou da hora de agir. Juntos.

A meta ousada do Intercept para 2025 é nada menos que derrotar o golpe em andamento antes que ele conclua sua missão. Para isso, dependemos do apoio de nossos leitores.

Você está pronto para combater a máquina bilionária da extrema direita ao nosso lado? Faça uma doação hoje mesmo.